Today, Colorado is experiencing record growth in its urban areas. But a century ago, many of those who moved to Colorado came to homestead and farm on the eastern plains. They were lured by the Homestead Act, which became an important factor in the development of our state.

Colorado Territory was only a year old in 1862, when the United States passed the Homestead Act. As the nation expanded westward, large amounts of land were held by the federal government. The Homestead Act provided an incentive for settlement of these lands. The Colorado Encyclopedia explains,

The Homestead Act of May 20, 1862, was the first act that enabled land acquisition from the public domain with no cost except filing fees. The concepts behind the Homestead Act were to facilitate the growth of an agrarian society by encouraging free farmers as opposed to slave-based agriculture. With the Southern states seceding from the Union and the slavery issue removed, the government could pursue such an approach to land acquisition. The act went into effect on January 1, 1863, the same day that President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

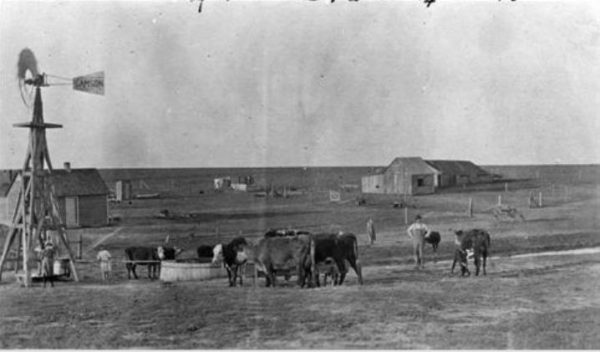

Settlers were allotted 160 acres of public domain lands in exchange for a small filing fee and an agreement to “prove up,” or reside on and farm on the land for five years before being granted full ownership. By 1900, 80 million acres of homestead land had been distributed.

A 1909 amendment to the Homestead Act had a significant effect on Colorado’s eastern plains. By that time, most of the West’s best farmland – that nearest rivers and streams – had already been claimed. So, to encourage farming of the remaining drylands, the Enlarged Homestead Act doubled the number of acres a settler could claim in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Arizona, Montana, Washington, Oregon, and Nevada, provided they agreed to farm those areas the government designated as non-irrigable.

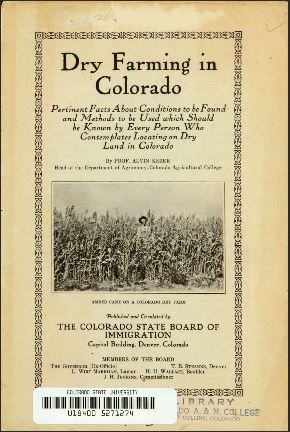

Just a few months after the Enlarged Act’s passage, the Colorado Agricultural Experiment Station issued Dry Land Farming in Eastern Colorado, a booklet of farming basics for new settlers, including those who had never farmed before. The Experiment Station also published “Hints to Plains Settlers,” a series of bulletins that included topics such as The Home Garden; Sod Crops; Summer Culture to Conserve Moisture; Windmill Irrigation; and The Cow as an Assistant. Other Experiment Station publications that dealt with dry farming included Notes on a Dry Land Orchard; Thorough Tillage System for the Plains of Colorado; Trials of Macaroni Wheat by Dry Farming; Suggestions to the Dry-Land Farmer; and others, which are available online from our library. The State Board of Immigration also provided settlers with tips on dry farming in their 1917 booklet, Dry Farming in Colorado.

In order to grow crops on land that had previously been thought only suitable for grazing, settlers had to experiment with new farming techniques. These included “deep plowing, compacting, summer fallowing, and seeding drought-resistant crops,” according to an article from the National Archives. However, these techniques only worked if enough rain fell. In one of their publications the Experiment Station’s director, L. G. Carpenter, warned settlers that “there are many chances of failure,” and that their best chance of success would come from focusing on dairying and poultry raising, with crops as an “adjunct.” Many settlers, however, failed to heed his warning. Dryland farming damaged the land and led to significant erosion, which culminated in the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

Homesteading was abolished by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, except for in Alaska, where it was allowed for another ten years. For a little over a century, however, the Homestead Act had made a significant contribution to the shaping of Colorado and the West. To learn more about the lives of homesteaders in Colorado, a great book is Long Vistas: Women and Families on Colorado Homesteads, which you can check out from our library.